Reading, Writing, Thinking: Just Selfish Means of Survival?

The other day I was thinking to myself in one of my many imagined conversations with someone (could be anyone, really; a colleague, the wooden head, my alter ego, whomever or whatever), that the act of reading is an act of creativity, almost brutal in some sense, and, depending on how practiced you are, extremely rewarding if not altogether mentally exhausting—which lead me to consider how all of this (reading, writing, abstract thinking, etc.) could simply be a selfish means of survival for our precarious little neurons.

The other day I was thinking to myself in one of my many imagined conversations with someone (could be anyone, really; a colleague, the wooden head, my alter ego, whomever or whatever), that the act of reading is an act of creativity, almost brutal in some sense, and, depending on how practiced you are, extremely rewarding if not altogether mentally exhausting—which lead me to consider how all of this (reading, writing, abstract thinking, etc.) could simply be a selfish means of survival for our precarious little neurons.

The little devil (the devil's advocate, as it were) who speaks up in defiance whenever I plead my cases, which is to say make my mental arguments (I need to really watch myself closely these days because sometimes I can be seen almost talking to myself as my lips move while my eyes just sort of waggle off into space without focus), in this case asks me how can reading be a creative act? You just sit there. Well, of course you just sit there, I retort, otherwise you could have a serious accident, say, if you were to try and drive or jog about with book in hand!

But the very act of reading, if you do it well (and I think you can apply this to any sort of work, fiction or non, as long as you avoid crap), requires you to build foundations from all the raw (and perhaps not-so raw) material of your imagination in order for any of the ideas to make sense. As you read you keep building and shaping and rebuilding and reshaping. Maybe you even have to tear some things down, things that you constructed from incorrect assumptions. Perhaps you can liken the idea of this building and constructing of ideas to creating an image of the work's setting, whatever that means. Then, if you consider fiction, or really any work that contains rich characterization, you have to literally create this character, this human being in your mind from only the bits and pieces provided to you by the author. But that's also the reason we read, too. We read to create as we do anything else.

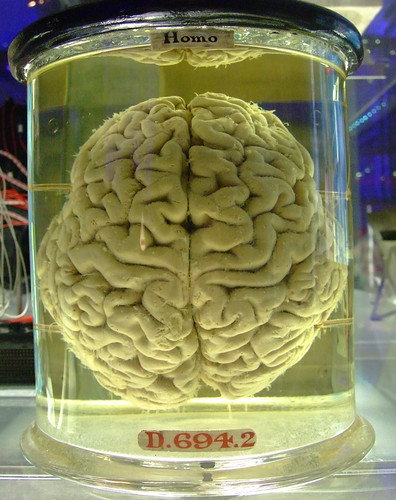

Perhaps books (really language and its eventual persistence, e.g. writing) were somehow a necessary outcome of the evolving human mind. We humans seem to have this need to build, explore, create, etc., almost to the exclusion of anything else, but, biologically and fundamentally, so does life. I mean it moves—it's animated. It seeks and creates for itself a means to continue (back to that fundamental point to all life, survival) as well as recreates in order its kind to perpetuate. Now think neurons in the brain. The fundamental function of neurons is to connect with other neurons (okay, I'm no expert in Neuroscience) via synapses and then to stimulate one another by secreting neurotransmitters. This sort of thing is done in the brain all the time, especially when one's imagination is working and when one learns and works. This is a kind of “survival” of the neuron, or a continuation; an act of creation, if you like, which is to say the forming of a connection where before there was none. It seems to be the neuron's purpose, at any rate.

I was thinking that for some reason our ability to process language (communicate with one another, think symbolically, write, etc.) at such levels beyond the simple, “apparent” reasons for survival (i.e. why didn't we evolve with just enough capacity to survive what we needed to survive?) , is perhaps for more selfish reasons. Perhaps we are what we are simply because we need to be, and for no grander reason than the specific makeup of our human brains, in order for those little neurons to keep connecting as they do, requires us to be this way. Natural selection brought us to a certain point (accidentally?) and now here we are, “conscious” as we are for no other reason than to simply reason, for the sake of reasoning, in order to perpetuate, continue, as with all life, in a purely biological sense.

In my mind I keep seeing these eagerly awaiting, pulsing neurons “wanting” to connect, almost rabid with desire. Imagine that some early human mutations had brains whose neurons made had the ability to make connections so very quickly and efficiently (this is how I imagine a super-intelligent person's brain to be configured, but I have no idea), but that while there was the very real, day to day struggle to survive (forage for food, fight off predators, find shelter, etc.), there was little else for this person's mind to process. Language was still too rudimentary, if it existed at all, and so while common foods might have been known by some associative abstraction (a marking, some primal grunts, etc.), there was nothing to learn, no “symbols” that could be used to associate things in reality with “mental concepts” and so, perhaps, a brain so configured (e.g. genetically predisposed to quickly and efficiently make connections) simply starved (there are cases today, extremely rare, who are born with immeasurably large Iqs, but even with all there is to absorb through books, etc., still go mad because there is no one with whom these people can talk; they are, for all their intelligence, literally mentally handicapped.) Someone born like that back then could go quickly insane; others in the tribe (or whatever you'd call the collective) would probably end up killing the poor guy or abandoning him; this, at least perhaps, before the ideas of the shaman, medicine men, ritual, spirit worlds (in general, repetition, pattern, etc.)

Over time, though, as our stubborn genes persisted and somehow equalized (normalized/found balance), we began to build the foundations (the ideas of repetition, for example, which leads to patterns, or perhaps its the recognition of patterns and repetition that lead to these ideas, were probably key), or scaffolding, to foster such brain chemistry so that our strange “creative,” “intelligent” minds (with their super-fast-connecting neurons) could persist, continue, survive longer than they previously had.

It's interesting how we learn so easily from pattern. I mean, for example, if you play a basic rhythm on some drums and watch how people react, they begin by tapping along with their feet and “counter beating” by, maybe, clapping their hands; i.e. they begin to mimic, repeat, copy, the rhythm. In other words they come to understand it, or learn it (the various new pathways in the brain having been created by newly formed connections between the neurons which now recognize the rhythm as a pattern of sound that now enable one to recall the pattern at the same time as it is being repeated externally on the drums by the performer).

So we hear, we eventually reproduce by playing along and then we can later recall and repeat. Of course one of the most important things to note, too, is that we also “improvise” over or on top of the beat. Which is to say that we create a new kind of pattern that doesn't necessarily deviate too much from the original, but rather complements it, and which is played on top of the learned rhythm. From that point, for some reason, once we know that we can keep the beat or create it ourselves without the need of the external stimulus (the drummer) we not only reproduce the learned beat and improvise on top of the beat, but we come to understand that we can create a whole “new” beat. (I have some questions here regarding whether or not this is actually the case but for now I assume that we can spontaneously create whole new beats (rhythms) from learning to reproduce a rhythm of another kind).

So we have the means now to mimic, improvise and create, and thus our neurons have the means to make all sorts of new connections based on these patterns, learned or synthesized. Back to books and my original ideas that lead me on this ghastly strange tangent. Language, communication, making sounds, persisting language so that it can be passed on (first in the oral traditions of story telling, then in writing, etc.) is merely all a means to keep the selfish neurons connecting and continuing their excitations and their neurotransmissions and we are just along for the ride, whether we like it or not.

And so it was when the first bright mind awoke to a small band of mostly mute, early humans so long ago and cried out in helpless, gurgling spasms for want of something it couldn't possibly yet understand, little could it know, as it was being bludgeoned to death by its dim-witted peers, that its lesser kin were about to pave the way via their genetic material toward its very salvation--eventually.